Introduction

Welcome to “The PC Emulation Book.”

This document aims to become a comprehensive guide to emulating the original models of the IBM Personal Computer:

- The IBM Model 5150 Personal Computer

- The IBM Model 5160 Personal Computer XT

🚧 UNDER CONSTRUCTION! 🚧

You’ll notice that many of the pages in this book are empty stubs. Content is still being fleshed out. Here is a list of some of the more complete pages:

- The Intel 8253 Programmable Interval Timer

- The Intel 8259 Programmable Interrupt Controller

- The Keyboard

Why Emulate the PC?

The IBM PC is arguably one of the most influential computers in history, establishing standards that enabled the proliferation of “PC-compatible” systems and cemented the very term “PC” as an Intel-based system, probably running a Microsoft operating system. The “PC” lives on even today, only recently challenged for supremacy by the rise of ARM-based CPUs.

The PC was an open and well-documented system. IBM published full schematics and commented BIOS source code listings, allowing anyone to understand in great detail how the system operated, even without owning the physical hardware.

There are thousands of software titles to explore on a PC emulator, although the PC’s limited graphics and sound capabilities make many of the games for the platform less than spectacular. Still, there are some classic titles that are still fun to play today, such as AlleyCat and Digger.

If you’re up for a challenge, recently several demos have been released that push the original PC hardware to its utter limits and require cycle-exact emulation of the 5150 and its components. These demos include 8088 MPH, released in 2015, and Area 5150, released in 2022.

Even without any attempt at cycle-accuracy, the PC can be emulated with a respectable level of compatibility.

What You’ll Learn

This book aims to cover the complete process of building a PC emulator from the ground up, including:

- Hardware Architecture: Understanding the IBM PC’s system design and component interactions

- CPU Emulation: Implementing the Intel 8088 processor

- Support Chips: Emulating the various Intel support chips that made the PC work

- Peripheral Devices: Implementing keyboards, displays, storage, and other I/O devices

- System Integration: Bringing all components together into a working emulator

Target Audience

This book is intended for emulator authors, but retro-developers may find it a useful reference as well, or anyone simply curious about how classic computers of the era worked.

Prerequisites

To get the most out of this book, you should have:

- A basic understanding of computer architecture concepts

- Familiarity with a high-performance programming language (C, C++, Rust, or similar)

- Basic understanding of digital logic

- Some experience with emulation

- If you have never programmed an emulator before, it is recommended that you start with the CHIP-8, a simple system that teaches basic emulation concepts. You can find a guide here.

License

This book is open-source and all content is licensed under the CC0 1.0 Creative Commons Public Domain license, except where otherwise noted.

Contributing

The main source repository for the PC Emulation Book can be found here.

IBM PC/XT Architecture Overview

The design of the IBM 5150 Personal Computer reflects IBM’s project requirements to create a low-cost, maintainable system capable of expansion.

CPU

IBM chose the Intel 8088 for the 5150. The 8088 was a lower-cost variant of the 8086 CPU. While still 16-bit internally, the 8088 only had an 8-bit data bus. This simplified the 5150’s motherboard design, and made it easy to build a system around Intel’s various 8-bit peripheral chips.

The 8088 has 20 address lines, allowing it to address \(2^{20}\) bytes, or 1MB.

IBM chose to reserve addresses above 0xA0000, leading to the infamous “640KB” memory limit that is often mistakenly blamed on Microsoft.

Expansion Bus

The 8-bit data bus of the 8088 would also dictate the 8-bit data width of the system’s expansion bus. This bus would later be expanded to 16-bits with the IBM 5170 AT, and would later be dubbed the ISA bus by Compaq1 and a growing consortium of PC clone manufacturers.

System Clock

The 5150 has a single main system crystal with a frequency of 14.31818MHz. This frequency is exactly four times the NTSC color subcarrier frequency.

The crystal frequency can be expressed as a fraction:

$$f_{crystal} = \frac{315}{22} \text{ MHz} = 14.318181\overline{81} \text{ MHz}$$

This choice was made to make the PC more easily compatible with North American television sets, making available a low-budget display option. This may seem like an odd choice for a business-oriented computer, but it allowed the IBM Color Graphics Adapter to omit a separate crystal.

The CPU frequency (4.77 MHz) is obtained by dividing the system clock by 3:

$$\frac{14.3181818}{3} = 4.773MHz$$

The 8088 was rated for 5MHz operation2, so this represents about a 5% underclock.

References

-

wikipedia.org Industry Standard Architecture. ↩

-

Intel Corporation. 8088 8-Bit Hmos Microprocessor. Intel Corporation, August 1990. Document Number: 231456-006. Available at: Intel 8088 Data Sheet PDF ↩

Memory Map

BIOS Data Area

ROM Layout

I/O Port Map

Intel 8088 CPU

Architecture and Registers

Instruction Set and Execution

Bus Interface and Timing

Intel 8259 Programmable Interrupt Controller

The Intel 8259 Programmable Interrupt Controller (PIC) plays an essential role in the operation of much of the hardware of the IBM PC. The PIC can be thought of as an expansion unit to the 8088’s single INTR pin, allowing 8 separate interrupt sources to be handled in a prioritized manner.

The PIC is a surprisingly challenging chip to emulate correctly, partially due to some ambiguities in its documentation.

Overview

The 8 inputs of the PIC are called Interrupt Request lines, which are often referred to as IRQs (Interrupt reQuest).

The PIC has three main 8-bit registers. Each bit in these registers corresponds to an IRQ with the least significant bit mapping to IRQ 0 and the most significant bit mapping to IRQ 7.

- Interrupt Request Register (IRR): This register holds bits reflecting the IRQ lines that are requesting service.

- Interrupt Mask Register (IMR): A

1bit set in this register prevents the corresponding IRQ line from being serviced. - In-Service Register (ISR): A

1bit set in this register indicates that the corresponding IRQ has been acknowledged by the CPU and is now “in-service”.

The 8 IRQs of the PIC are ordered in terms of priority, with IRQ 0 being the highest priority, and IRQ 7 being the lowest priority. This means that if IRQ 0 and IRQ 1 occur simultaneously, IRQ 0 will be serviced first.

This also means that it is possible for a higher priority interrupt to be serviced while a lower priority interrupt is already in service. Normally, the 8088 clears the I flag when executing an interrupt. If a programmer desires their interrupt service routine to be reentrant, they would need to issue an STI instruction to allow this to occur.

IBM PC PIC Configuration

IRQ Assignments

The IBM PC maps devices to the 8259’s IRQ lines as follows. Some of these connections are direct traces on the motherboard, other IRQs are connected to the ISA bus. In some cases, a peripheral card may have had a jumper to allow selection of a particular IRQ.

| IRQ | Connection | Device |

|---|---|---|

| IRQ 0 | Direct | System Timer |

| IRQ 1 | Direct | Keyboard Controller |

| IRQ 2 | ISA/Direct | Vsync Interrupt (EGA) or Secondary 8259 (AT) |

| IRQ 3 | ISA | Serial Port - COM2 |

| IRQ 4 | ISA | Serial Port - COM1 |

| IRQ 5 | ISA | Hard Disk Controller or LPT2 |

| IRQ 6 | ISA | Floppy Disk Controller |

| IRQ 7 | ISA | Parallel Port - LPT1 |

I/O Ports

The 8259 has a single address pin, A0, via which one of two registers can be selected.

The two registers are decoded by the PC at the following addresses:

| PC Port | 8259 Port | RW | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0x20 | 0 | RW | Command/Status Register |

| 0x21 | 1 | RW | Data/Mask Register |

The Unimportant Stuff

The 8259 was designed to be compatible not only with the 8088 and 8086, but with Intel’s earlier CPUs, the 8080 and 8085. There are various mode flag bits that control whether the 8259 should expect to be paired with an 8088 or not - obviously, on the IBM PC, you can expect these bits to be set properly, and emulation of the 8080 modes is certainly not required.

The 8259 supported daisy-chaining of additional 8259 chips to enable more interrupt sources to be handled - something that Intel called cascading. This was not used on the IBM PC, which only had a single 8259. Two 8259s were employed on the IBM 5170 AT in a primary/secondary configuration. Obviously this is something you do not need to emulate either.

The PIC can be operated in edge-triggered or level-triggered mode. The IBM PC exclusively operates in edge-triggered mode, but implementing level-triggered mode is fairly trivial to do.

There are additional features like priority rotation and special mask mode which are not used by the IBM PC.

Interrupt Processing Logic

The important thing to understand about the PIC is that it is implemented as an array of 8 priority cell circuits. The IRR, IMR, and ISR “registers” are simply latches within each priority cell. This means that a good part of the interrupt evaluation logic happens continuously, since it is simply driven by immediate state of the circuit. The PIC has no clock input, so all it can do is respond to changes of its input pins. With one exception - but we’ll talk about that later.

Let’s look at an example of interrupt logic flow:

The Simple Version

- A device raises its IRQ line connected to the PIC.

- The PIC looks to see if that IRQ is masked off in the IMR, if it is already in service, or if a higher-priority interrupt is in service, in which case the interrupt cannot be serviced at the moment.

- If the IRQ can be serviced, the PIC raises the INTR line to the CPU.

- The CPU acknowledges the interrupt and the PIC sets the corresponding bit in the ISR to indicate that the interrupt is now in service. The corresponding bit in the IRR is cleared to indicate the IRQ is no longer requesting service.

- The CPU executes the interrupt based on the 8-bit vector the PIC provides in response to the CPU’s interrupt acknowledgement.

- The interrupt service routine executes. When it is done, it sends an

End-of-Interrupt (EOI)command to the PIC. - The PIC clears the corresponding bit in the

ISRindicating that the interrupt has completed servicing.

The original IRQ line may remain high at this point, but in the PC’s standard edge-triggered mode it will not be serviced again until it transitions low and then high again.

The Detailed Version

- A device raises its IRQ line connected to the PIC.

- The low-to-high transition of the IRQ line sets the IRQ’s edge latch and sets the corresponding bit in the

IRR.- If the corresponding bit in the

IMRis set, the signal from theIRRdoes not propagate further. - If the corresponding bit in the

IMRis clear, the signal from theIRRreaches thePriority Resolver.

- If the corresponding bit in the

- The priority resolver checks to see if the corresponding bit in the

ISRis set, or if any bits lower than the corresponding bit are set, indicating a higher priority interrupt is already in service.- If any of these bits are set, nothing further happens for the moment.

- If none of these bits are set, the priority resolver will instruct the control logic to raise the PIC’s INTR pin, which is connected to the CPU.

- The CPU finishes an instruction, at which point it samples the INTR pin.

- The CPU notices INTR is high.

- If the CPU’s

Iflag is cleared, it ignores INTR being high and continues execution as normal.

- If the CPU’s

- The CPU begins to acknowledge the interrupt.

- The CPU issues one bus cycle with the

INTAbus status encoded. - The CPU bus controller decodes the

INTAbus status and asserts the physical \(\overline{INTA}\) pin.

- The CPU issues one bus cycle with the

- The PIC detects the \(\overline{INTA}\) pin going high.

- The priority resolver sets the highest-priority bit in the

ISRto indicate that the interrupt is entering service. - In edge-triggered mode, the priority resolver clears the corresponding bit in the

IRR.

- This is the only difference between edge-triggered mode and level-triggered mode.

- The control logic asserts the internal \(\overline{FREEZE}\) signal. This prevents any change to any bit in the

IRRwhile the interrupt acknowledge process is active.

- The priority resolver sets the highest-priority bit in the

- The \(\overline{INTA}\) pin goes low as the CPU completes the INTA bus cycle.

- The \(\overline{INTA}\) pin goes high again as the CPU issues a second INTA bus cycle.

- The PIC emits the 8-bit interrupt vector which the CPU reads during the second INTA bus cycle.

- The \(\overline{INTA}\) pin goes low as the CPU completes the second INTA bus cycle.

- The control logic de-asserts the \(\overline{FREEZE}\) signal, allowing the

IRRto update again. - In auto-EOI mode, the priority resolver clears the corresponding

ISRbit.

- The control logic de-asserts the \(\overline{FREEZE}\) signal, allowing the

- The CPU uses the interrupt vector received from the PIC to look up a far pointer to the correct Interrupt Service Routine from the Interrupt Vector Table.

- The CPU clears the

IandTflags, then jumps to the interrupt service routine. - At the end of the interrupt service routine, the routine sends an

EOIcommand to the PIC. - The PIC clears the appropriate bit in the

ISRto indicate that the interrupt has completed servicing.

The Intel 8253 Programmable Interval Timer

The 8253 Programmable Interval Timer (PIT) is responsible for a number of tasks on the IBM PC. It maintains the system time, drives DRAM refresh, and controls the PC speaker to generate sound.

Overview

The PIT contains three independently operating 16-bit counters or ‘channels’, each capable of operating in different modes.

Physically, each timer channel is assigned a clock input, a gate pin, and an output pin (OUT). The gate pin can be used to control or disable counting in specific modes.

Counters are operated by first configuring them by writing a Control Word to the 8253’s Control Word Register. Then, an initial count - often referred to as a ‘reload value’ - is written directly to the timer channel port. A counter has a full 16-bit range, as an initial count of 0 is treated as a count of 65,536 in binary mode or \(10^4\) in BCD mode.

Once configured and running, on each tick of the channel’s clock input, the channel’s internal Counting Element decrements. When the counter reaches 0 (or 1 in some modes), some specific behavior will be triggered (depending on mode), usually changing the state of the channel’s output pin.

The current value of a counter channel can be read at any time by reading from the channel’s specified port.

Pinout

Figure 1: Intel 8253 Pinout

The 8253 has an 8-bit data bus by which you read and write the chip’s registers, which are selected by the A0 and A1 pins.

IBM PC Timer Configuration

The 8253 has three independent clock input pins, allowing each counter to be driven at a different frequency. The IBM PC ties all three clock inputs to the same clock line, which runs at the system crystal frequency divided by 12.

$$f_{timer} = \frac{\frac{315}{22}}{12} \text{ MHz} = 1.19318\overline{18} \text{ MHz}$$

Note: Other systems that use the 8253 can connect these timer clock inputs in different ways - even connecting one timer channel output to the clock input of another to act as a clock divisor.

| Timer | Purpose | Frequency | Connection |

|---|---|---|---|

| Timer 0 | System Timer | 18.2 Hz | System Timer Interrupt |

| Timer 1 | DRAM Refresh | 15 μs | DMA Controller for memory refresh |

| Timer 2 | Speaker | Variable | PC Speaker output |

Timer 0

Timer 0’s OUT pin is directly connected to the IR0 pin of the 8259A Programmable Interrupt Controller. When the Timer 0 OUT pin has a low-to-high transition, this will trigger an IRQ0. This causes an interrupt 8, which normally is configured to maintain the system’s time of day clock by the BIOS.

The BIOS initializes Timer 0 to a reload value of 0 (65,536)

$$ T = \frac{65536}{1.19318\overline{18}\times 10^{6}} \approx 0.0549254\ \text{s} $$

$$ T \approx 54.93\ \text{ms} $$

$$ \frac{1\text{s}}{54.93\text{ms}} \approx 18.2Hz $$

This will cause an Interrupt 8 to execute 18.2 times per second.

Many applications, especially games, will use Timer 0 for their own purposes, and so the time of day clock was notoriously inaccurate without being synchronized to a realtime clock module.

Timer 0’s GATE pin is tied to +5v.

Timer 1

Timer 1’s OUT pin connects to a 74LS74 flip-flop which latches its output. The output of this flip flop is connected to the DRQ0 pin of the 8237 DMA Controller, and is reset by the \(\overline{\text{DACK0}}\) signal. This causes one DMA transfer to occur in read mode, which refreshes the system’s DRAM.

The BIOS initializes Timer 1 to a reload value of 18:

$$ T = \frac{18}{1.19318\overline{18}\times 10^{6}} \approx 0.0000151\ \text{s} $$

$$ T \approx 15.1\ \text{μs} $$

$$ \frac{1\text{s}}{15.1\times 10^{-6}\text{s}} \approx 66.2\text{KHz} $$

This will cause a DMA refresh request approximately every 15 microseconds, or every 72 clock cycles. If this sounds like a lot, it is. The DRAM refresh process robs the 8088 of about 5-6% of its performance, depending on bus activity.

Note: You can ignore this channel if you are not interested in cycle-accuracy. However, the IBM PC BIOS does check that Timer 1 is running by checking that the DMA channel 0 is counting. You can hack your way around this test by just making the DMA channel 0 count on read.

Timer 1’s GATE pin is tied to +5v.

Timer 2

Timer 2’s OUT pin connects to the PC’s speaker and cassette interface circuitry. Timer 2 is typically configured to produce square waves to drive the speaker to play notes of specific frequencies, and Timer 2’s GATE input can be used to silence the speaker when desired.

For more details, see the PC Speaker chapter.

Timer 2’s GATE pin is tied to the 8255 PPI’s Port B, Bit 0 (Pin #18).

I/O Ports

The 8253 has two address lines, A0 and A1, which allow selection of four ports.

These four ports are decoded by the PC at the following addresses:

| PC Port | 8253 Port | RW | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0x40 | 0 | RW | Timer 0 Count Register |

| 0x41 | 1 | RW | Timer 1 Count Register |

| 0x42 | 2 | RW | Timer 2 Count Register |

| 0x43 | 3 | W | Control Word Register |

Control Word Format

The 8253’s control word can be written to at port 0x43 and is used to configure one of the three counters, each of which can be configured with different modes.

Figure 2: Intel 8253 Control Word Format

The specified channel’s counting mode, IO mode, and whether or not it should count in BCD, is configured with a single 8-bit write. Note that using 0b11 as the timer selection is invalid on the 8253. On the 8254, it selects the read-back command, which will not be covered here.

Counter Channel Configuration

Binary vs BCD Mode

A timer channel can be configured to count in either binary or Binary Coded Decimal (BCD) mode. I have not seen any software that actually uses BCD mode. When writing your initial 8253 implementation, you can probably ignore BCD mode.

RW Mode

A timer channel can be configured for 16-bit read/writes in LSBMSB mode using 0b11 in the RW field, or in one of two 8-bit read/write modes:

LSB(0b01):- On write, an 8-bit value is used to initialize the \(\text{CR}_l\) register, which holds the least significant 8 bits of the initial 16-bit count.

- On read, the contents of the \(\text{O}_l\) register are returned. See Counter Channel Operation.

MSB(0b10):- On write, an 8-bit value is used to initialize the \(\text{CR}_m\) register, which holds the most significant 8 bits of the initial 16-bit count.

- On read, the contents of the \(\text{O}_m\) register are returned. See Counter Channel Operation.

The 8-bit RW modes allow programming a timer channel with fewer writes. In MSB mode, the full range of a timer channel is available, with reduced granularity.

Note: The RW mode of a channel does not affect its basic counting operation. It remains a full 16-bit counter internally regardless of input mode.

In LSBMSB mode, it takes two 8-bit writes to read or write to the timer channel. An internal latch keeps track of whether the initial LSB has been written. On a write, the first byte written is used to initialize the \(\text{CR}_l\) register. The second byte initializes the \(\text{CR}_m\) register. On a read, the first read returns the \(\text{O}_l\) register, the second read returns the \(\text{O}_m\) register.

Warning: The 8253 cannot handle interleaved 16-bit read and write operations. In

LSBMSBmode if you write one byte and then read one byte without completing the write operation, you will receive random data. Some software has been observed improperly operating the 8253 in this way, especially software designed for the 8254 which did not have this limitation. Ensure that your 8253 can recover in this scenario - what value you decide to return is up to you - the actual value is nondeterministic “open bus” behavior internal to the chip.

Counter Latch Command

There is a small matter of concern when a channel is configured for LSBMSB mode. Since it takes two bytes to read the full 16-bit counter value, it is possible that the counter can decrement between the time the first byte is read and the second. Therefore, a Counter Latch command is provided. The Counter Latch command is sent by setting the RW field of the control word to 0b00. This does not change the counter channel’s configuration otherwise - the Mode and BCD bits are ignored when sending the counter latch command. See the Counter Latch Operation section below for how the latching is implemented.

Counter Channel Operation

Figure 3: Intel 8253 Counter Block Diagram

There are a few important things to note in the channel block diagram above. The heart of the counter is the Counting Element (CE). This is a 16-bit synchronous down-counter that contains the current count value. Above the CE are \(\text{CR}_m\) and \(\text{CR}_l\), two halves of the Count Register (CR). The CR holds the initially configured count, and is used to reload the CE on terminal count in modes that do so.

The count value is transferred from the CR to the CE when a full write of the CR is complete. This may require one or two bytes, depending on the configured RW Mode.

Both Count Registers are initialized to 0 whenever a channel’s mode is set. This avoids leaving either of the CR registers in an indeterminate state when using either byte RW mode.

Counter Loading

Counter loading is not instantaneous on write. A CR is not loaded until the 8253 sees a full clock cycle with a rising and falling edge after the write occurs. If the specific mode requires that the CE be loaded immediately from the CR, all 16-bits are transferred at once.

A count can be loaded with any 16-bit value from 0-65,535. To allow a full 16-bit range, a count value of 0 is interpreted by the 8253 as a count value of 65536.

Counter Latch Operation

Below the CE are \(\text{O}_m\) and \(\text{O}_l\), two halves of the Output Latch. When reading the count value from a channel, we are actually reading from the output latch. Typically, the output latch is updated each time the CE changes. When the Counter Latch Command is issued, the CE simply stops updating the Output Latch, essentially “freezing” the value inside at the point in which the latch command was issued.

When the Output Latch is fully read, which may take one or two bytes depending on the configured RW Mode, the Output Latch is “unfrozen” and will resume being updated by the CE on every tick.

The Output Latch operation can only be reset by fully reading the Output Latch. Issuing a new Counter Latch command will be ignored until the Output Latch is fully read.

Clocking Logic

An 8253 timer channel generally takes an action, such as transferring the CR to CE or decrementing the CE on the next falling edge of its input clock.

Counter Operating Modes

Timer channels can be set to any of 6 different modes.

- Mode 0: Interrupt on Terminal Count

- Mode 1: Hardware Retriggerable One-Shot

- Mode 2: Rate Generator

- Mode 3: Square Wave Generator

- Mode 4: Software Triggered Strobe

- Mode 5: Hardware Triggered Strobe (Retriggerable)

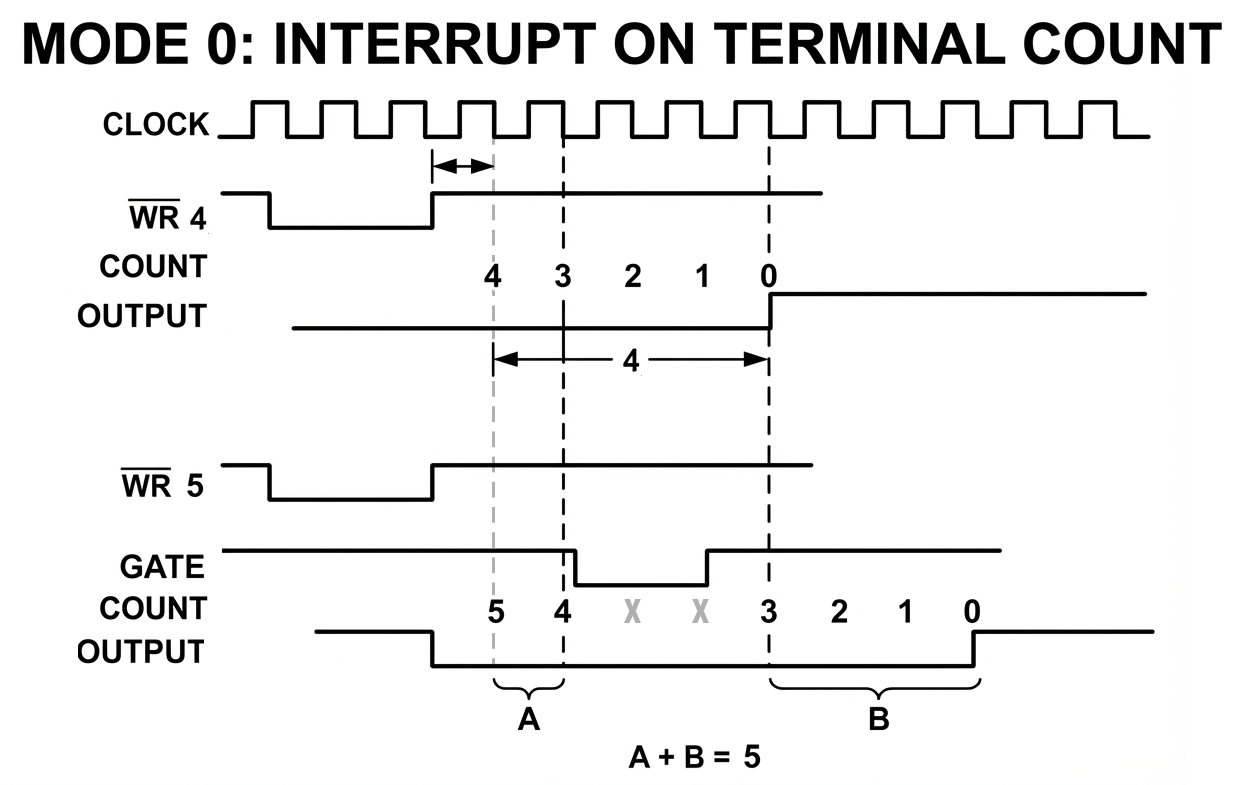

Mode 0 — Interrupt on Terminal Count

Upon setting this mode, OUT is initially LOW. This is the only mode where the initial OUT state is LOW after a mode is set.

In Mode 0, the counter counts down once per tick from the initial count until it reaches 0. When it reaches 0, OUT goes high and stays high until reprogrammed. The counter will continue to count, rolling over from 0 to 0xFFFF, but no longer affects the state of the OUT pin.

Note: The word “Interrupt” in this mode name can be a little misleading. Nothing about this mode is specific to generating interrupts. Interrupts are generated whenever timer channel 0’s output has a rising edge. Therefore, any operating mode can generate interrupts with timer channel 0. Additionally, using the Interrupt on Terminal Count mode on any other timer channel will not generate an interrupt.

Count Loading

- After setting the mode and initial count, the CR will be loaded into the CE on the next clock edge after the final write of the initial count.

Output Behavior

- After mode set: OUT → LOW

- When countdown reaches 0: OUT → HIGH (and remains HIGH)

- Upon writing new count: OUT → LOW

GATE Behavior

- Level-triggered

- GATE HIGH: enables counting

- GATE LOW: inhibits counting (freezes the countdown)

Reload Behavior

- In 8-bit RW modes:

- Writing either the

LSBorMSBwhile the counter is running forces OUT low immediately. - The CR will be loaded into the CE on the next clock edge.

- Writing either the

- In

LSBMSBRW mode:- Writing the

LSBwhile the counter is running disables counting and forces OUT low immediately. - Writing the

MSBwill load the CR into the CE on the next clock edge.

- Writing the

Timing

- For initial count = N, OUT will go high up to N+1 timer clock cycles after the write.

Figure 4: Timer Mode 0 - Interrupt on Terminal Count Timing

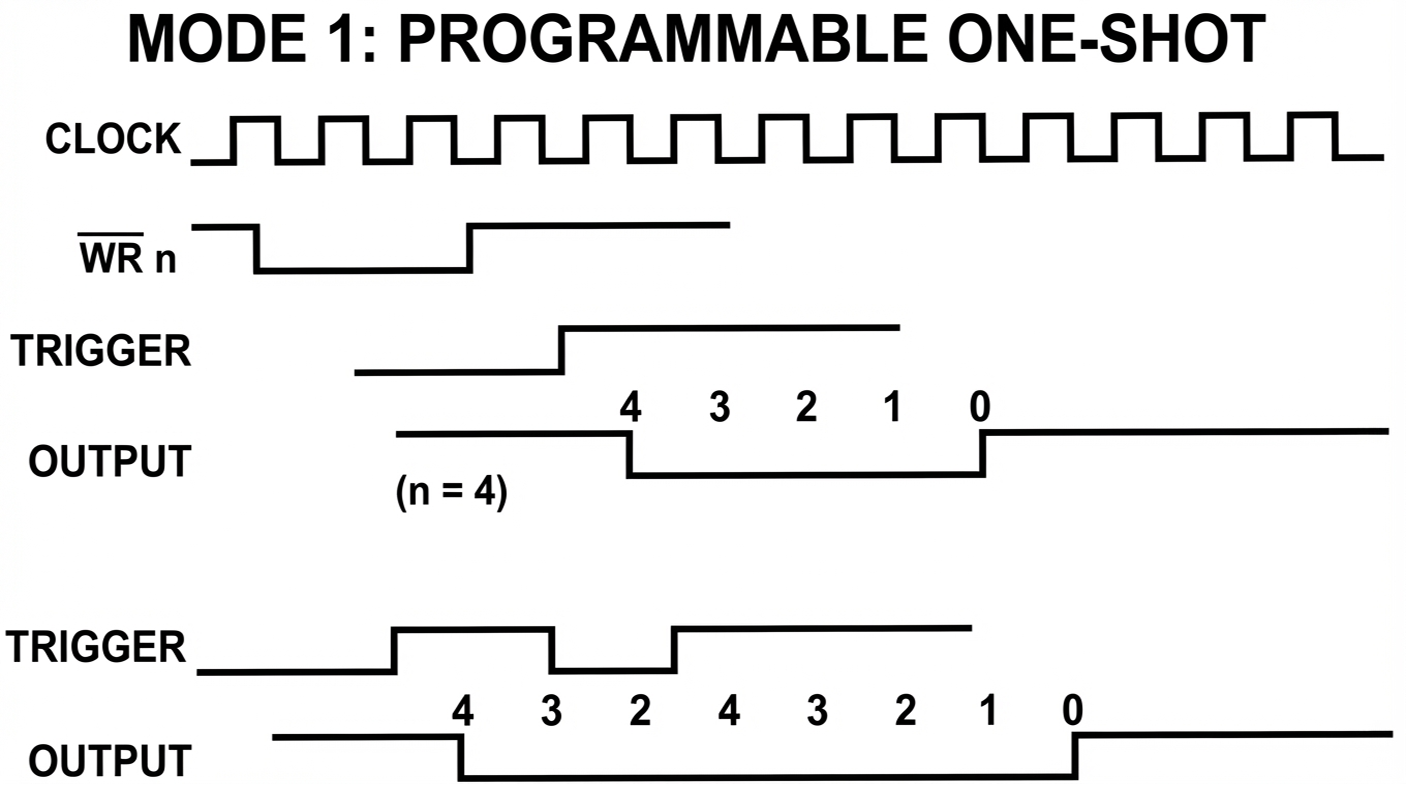

Mode 1 — Hardware Retriggerable One-Shot

Summary

This mode allows a low pulse of the OUT pin of a configurable length, triggerable via the GATE pin. This mode is inoperable on the IBM PC except on timer channel 2.

Upon setting this mode, OUT is initially HIGH. A rising edge of the GATE input will trigger OUT → LOW on the next clock edge. When the count reaches 0, OUT → HIGH. The counter will continue to count, rolling over from 0 to 0xFFFF, but will not affect the state of the OUT pin until the counter is re-triggered.

We refer to a “trigger” as a LOW → HIGH transition of the GATE pin.

Note: The count starts running as soon as Mode 1 is selected - but you’ll note that the CE is not loaded until a GATE trigger. Presumably, the counting element still contains whatever it had in it when the mode was set, but this has not been verified.

Count Loading

- After setting the mode and initial count, the CR will hold the initial count but will NOT write it into the CE until a trigger occurs.

Output Behavior

- After mode set: OUT → HIGH

- After GATE LOW → HIGH: OUT → LOW

- At terminal count: OUT → HIGH

GATE Behavior

- Edge-triggered

- GATE LOW -> HIGH: Trigger. The CR is loaded into the CE on the next clock edge.

- Since the trigger reloads the CE, another trigger will restart any count in progress.

Reload Behavior

- Writing a new count during an active count will not affect the current count until the next trigger, as the trigger controls loading of the CE from CR.

Timing

Figure 5: Timer Mode 1 - Hardware Retriggerable One-Shot Timing

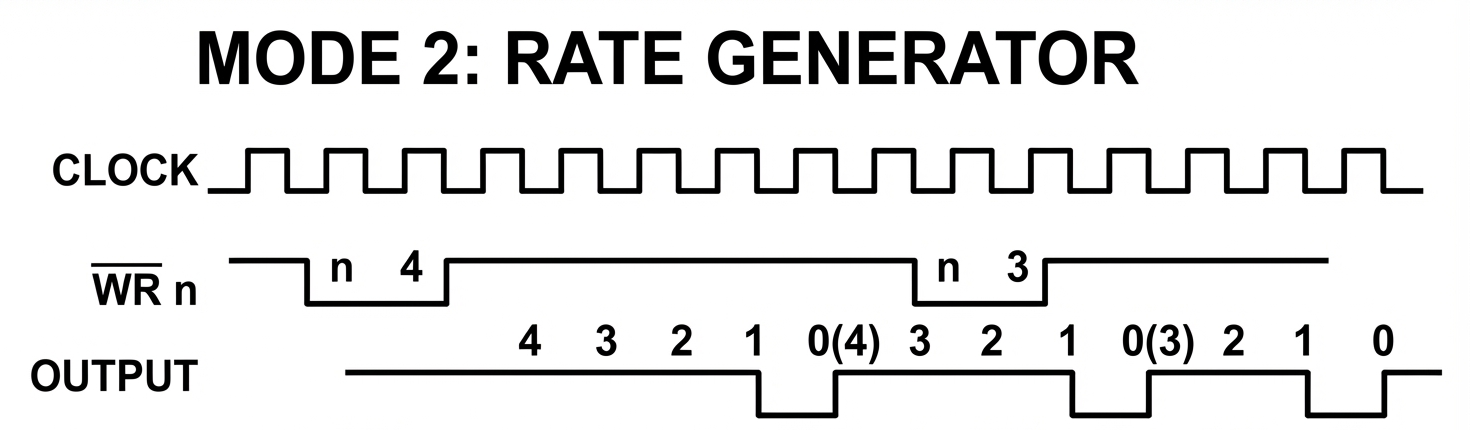

Mode 2 — Rate Generator

Summary

In this mode, OUT normally remains HIGH, but produces regular one-clock-wide low pulses. This mode is useful when a periodic LOW → HIGH transition is required.

On the IBM PC, timer channel 1 is typically configured for Mode 2 to repeatedly generate the \(DREQ0\) signal.

Output Behavior

- After mode set: OUT → HIGH

- When count reaches 1: OUT → LOW

- When count reaches 0: OUT → HIGH

GATE Behavior

- Edge-triggered

- GATE LOW -> HIGH: Trigger. The CR is loaded into the CE on the next clock edge. Counting enabled.

- GATE LOW: OUT is forced HIGH, counting disabled.

Reload Behavior

- Writing a new count during an active count will not affect the current count until either a terminal count or a GATE trigger.

- CR is automatically loaded into the CE after terminal count is reached, restarting the count.

Constraints

- A count of 1 is invalid and will cause the timer channel not to function.

Timing

Figure 5: Timer Mode 2 - Rate Generator Timing

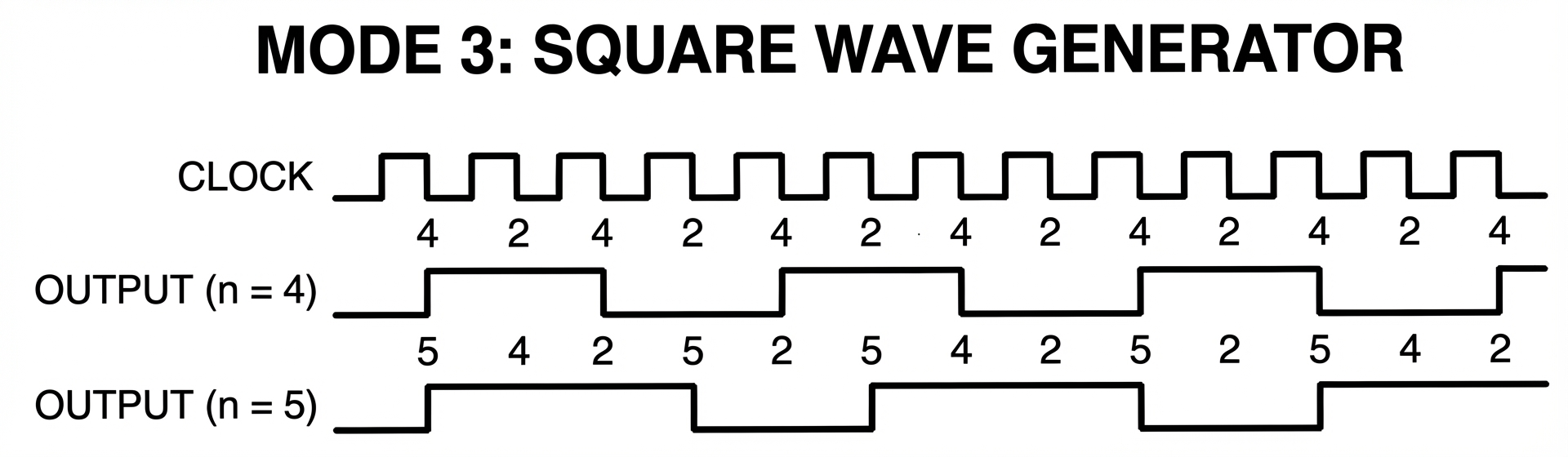

Mode 3 — Square Wave Generator

Summary

Similar to Mode 2, but produces a square wave: OUT alternates high and low with a 50% duty cycle (if the initial count is even). This is a general-purpose mode with many applications. The IBM BIOS sets timer channel 0 to Mode 3 to run the BIOS time-of-day clock. This mode can also be used to drive a tone of a specific frequency to the PC speaker on timer channel 2.

This mode is a bit more complex than the other modes. The 8253 creates a square wave of a period determined by the initial count by decrementing the counting element by 2 instead of 1. This presents a problem if the initial count is odd, as we need to reach 0 to trigger the terminal count condition.

Odd Count Logic

Within the counter is a flip-flop I will call the 1/3 flip-flop. This flip-flop is initially 0.

- If the CE is odd, the 8253 will decrement it as follows:

- If the 1/3 flip-flop is 0, the CE will be decremented by 1. This sets the CE to an even value.

- If the 1/3 flip-flop is 1, the CE will be decremented by 3. This sets the CE to an even value.

- If the CE is even, the 8253 will decrement it by 2.

- When the counter reaches terminal count (0), CE is reloaded by CR, and the 1/3 flip-flop is toggled.

This is a somewhat awkward way of accounting for the one missed clock period per cycle we would otherwise accumulate over time with an odd count. The result of this logic is that the resulting square wave is HIGH for \(\frac{N+1}{2}\) clocks and LOW for \(\frac{N-1}{2}\) clocks.

Note: The 8254 implements the logic for Mode 3 differently than the 8253. Refer to the 8254 datasheet for an accurate description if you are emulating an 8254.

The counter also has an output flip-flop that it uses in this mode to toggle the state of the OUT pin when terminal count is reached.

Output Behavior

- After mode set: OUT → HIGH

- At terminal count: OUT toggles state

GATE Behavior

- Edge-triggered

- GATE HIGH: Trigger. The CR is loaded into the CE on the next clock edge. Counting enabled.

- GATE LOW: OUT → HIGH. Counting disabled.

Reload Behavior

- Writing a new count during an active count will not affect the current count until either a terminal count or a GATE trigger.

- CR is automatically loaded into the CE after terminal count is reached, restarting the count.

Timing

Figure 6: Timer Mode 3 - Square Wave Generator Timing

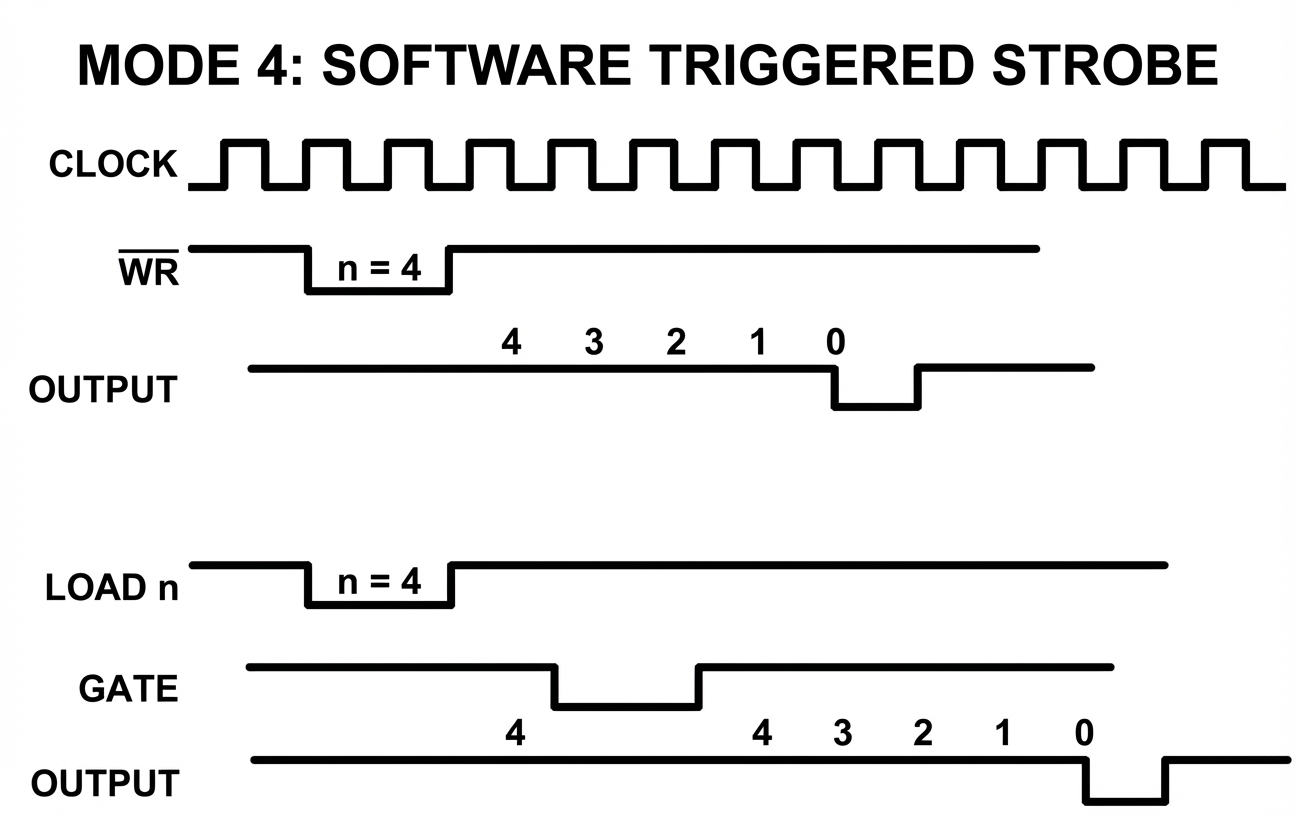

Mode 4 — Software Triggered Strobe

Summary

When the initial count reaches 0, OUT produces a one-clock-wide low pulse. This is similar to Mode 2, but with a distinct difference - in Mode 2, OUT goes low on a count of 1, and HIGH again on a count of 0. In Mode 4, OUT goes low on a count of 0, then HIGH again on the next clock edge. The counter will continue to count, rolling over from 0 to 0xFFFF, but will not affect the state of the OUT pin until the next count value is written.

Counting begins when the initial count is written (the “software trigger”).

Output Behavior

- After mode set: OUT → HIGH

- At terminal count: OUT → LOW for one clock period

Count Loading

- After writing the count, the CR is loaded into the CE on the next clock edge. Counting begins automatically on the following clock edge.

- Writing a new count during an active count will trigger a CR to be loaded into the CE at the next clock edge.

- In

LSBMSBmode, writing the first byte only has no effect.

- In

GATE Behavior

- Level-triggered

- GATE HIGH: Counting enabled.

- GATE LOW: Counting disabled.

- GATE does not affect OUT.

- GATE does not trigger a reload of the counter.

Timing

Figure 7: Timer Mode 4 - Software Triggered Strobe Timing

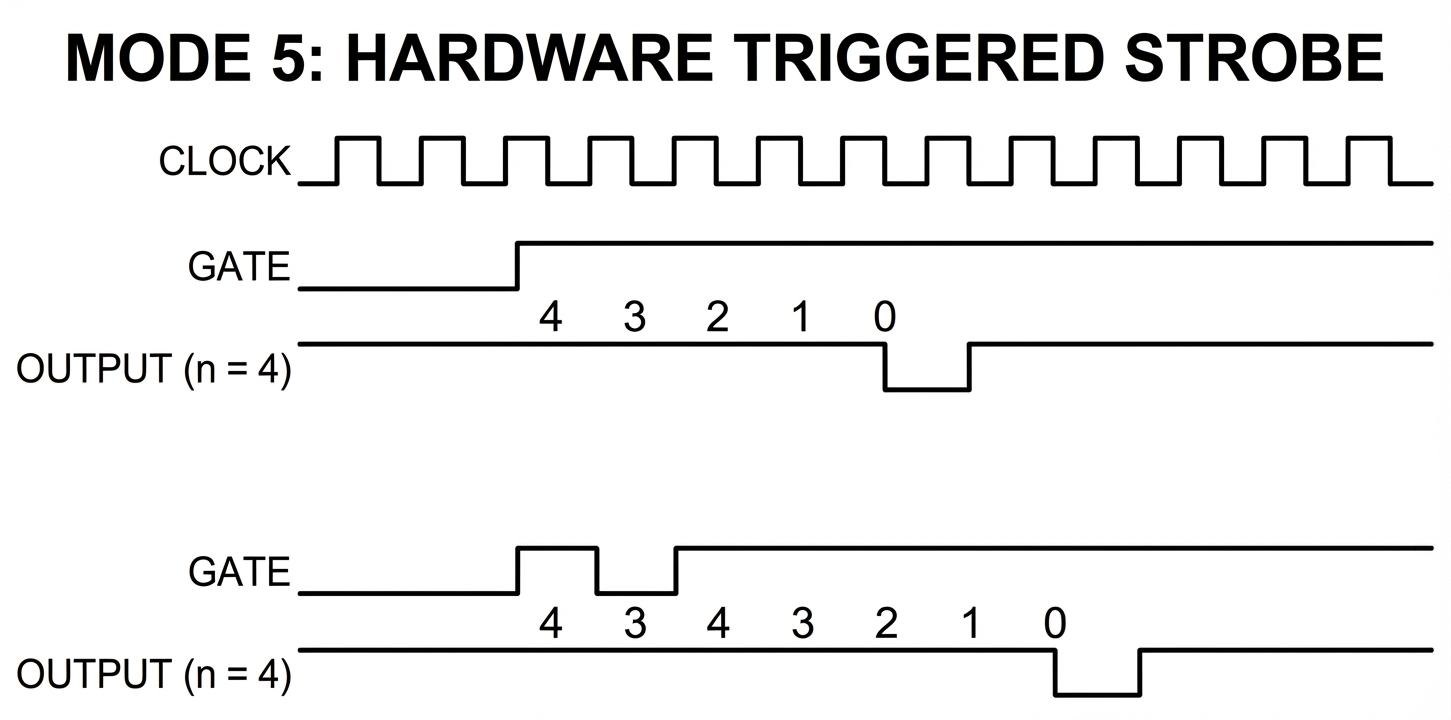

Mode 5 — Hardware Triggered Strobe

Summary

Similar to Mode 4, but triggered by a LOW → HIGH transition of GATE. In Mode 5, OUT goes low on a count of 0, then HIGH again on the next clock edge. The counter will continue to count, rolling over from 0 to 0xFFFF, but will not affect the state of the OUT pin until the counter is retriggered by the GATE pin.

Note: The count starts running as soon as Mode 5 is selected - but you’ll note that the CE is not loaded until a GATE trigger. Presumably, the counting element still contains whatever it had in it when the mode was set, but this has not been verified.

Output Behavior

- After mode set: OUT → HIGH

- At terminal count: OUT → LOW for one clock period

GATE Behavior

- Edge-triggered

- GATE LOW -> HIGH: Trigger. The CR is loaded into the CE on the next clock edge. Counting enabled.

- GATE does not affect OUT,

Reload Behavior

- Writing a new count value during an active count will not affect the current count until either a terminal count or a GATE trigger.

Timing

Figure 7: Timer Mode 5 - Hardware Triggered Strobe Timing

Mode Summary Table

| N | Mode | OUT after Mode set | GATE mode | Writing count reloads next clk | Automatic Reload | GATE initiates counting | GATE controls counting |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Interrupt on Terminal Count | LOW | Level-triggered | YES | NO | NO | YES |

| 1 | Hardware Retriggerable One Shot | HIGH | Edge-triggered | NO | NO | YES | NO |

| 2 | Rate Generator | HIGH | Both | NO | YES | YES | YES |

| 3 | Square Wave Generator | HIGH | Both | NO | YES | YES | YES |

| 4 | Software Triggered Strobe | HIGH | Level-triggered | YES | NO | NO | YES |

| 5 | Hardware Triggered Strobe | HIGH | Edge-triggered | NO | NO | YES | NO |

Edge Cases

Some interesting edge cases have been observed. Consider the following scenario:

- A timer channel is set to Mode 2 - Rate Generator, RW mode

LSBMSB, and an initial count written, starting the count. - Only the

LSBof a new count is written. - The timer reaches terminal count. What value is loaded into the Counting Element?

- Once the Counting Element has been reloaded, what happens when the

MSBof the new count is then written?

If you have studied the counter channel block diagram, you may be able to figure out what should happen. The \(\text{CR}_m\) and \(\text{CR}_l\) registers are used to hold the programmed initial count, and the CE is reloaded from these registers. In addition, the counter keeps a flip-flop to keep track of the progress of writing a new count, and will write the contents of the CR registers to the CE when the write is complete (depending on mode).

The Intel 8254

The 8254 is an improved model of the 8253 and was used in the IBM AT. It would become the standard timer chip in PC compatible systems for many years.

Changes in the 8254

- Faster clock inputs

- A channel state read-back command

- Resolves the issue with the 8253 where reads and writes to the same channel could not be interleaved without leaving the chip in an undefined state.

- Modified the logic of Mode 3 - Square Wave Generator.

If you wish to emulate the 8254 instead of the 8253, there’s no real problem with doing so.

Emulation Tips

Implementation Priority

- Implement these modes first:

- Mode 3, Square Wave Generator

- Mode 2, Rate Generator

- Mode 0, Interrupt on Terminal Count

- Connect the output of Timer Channel 0 to IRQ0

- Connect the 8255 PPI Port B bit 0 to the GATE of Timer Channel 2

Primary Emulation Resources

- (alldatasheet.com) 8253 Datasheet

- (alldatasheet.com) 8254 Datasheet

- (wiki.osdev.org): Programmable Interval Timer - Mostly describes the 8254

Further Reading

- (wikipedia.org): Intel 8253

- (intel.com @ archive.org): 8254/82C54 Programmable Interval Timer

References

Programmable Peripheral Interface (8255 PPI)

The Intel 8255 PPI is a general-purpose IO chip that provides 24 configurable, bidirectional I/O pins.

The 8255 was used in a number of systems, and even a few mouse controller cards.

The IBM 5150 and 5160 utilize the PPI to receive scancodes from the keyboard interface, read the system’s DIP switches, read motherboard status lines and write control signals.

The PPI is a moderately complex chip with several modes of operation. Perhaps unique to all the support chips you need to emulate, the vast majority of the PPI’s extended capabilities and modes can be completely ignored by a basic PC emulator.

Intel 8237 DMA Controller

The Intel 8237 DMA (Direct Memory Access) Controller enables efficient data transfers between memory and I/O devices without CPU intervention. In the IBM PC, it coordinates data transfer to and from floppy and hard drives, as well as performing DRAM refresh cycles.

Overview

The 8237 provides four independent DMA channels, each capable of transferring data between memory and peripherals. In theory, the 8237 is capable of performing memory-to-memory transfers as well, but its implementation in the IBM PC prevents it from doing so.

IBM PC DMA Configuration

| Channel | Purpose | Device |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Memory Refresh | DRAM |

| 1 | Unused | - |

| 2 | Floppy Disk | FDC |

| 3 | Hard Disk* | HDC |

Note: Not all hard disk controllers use DMA. Notably, most models of the XTIDE do not.

Hardware Interface

I/O Ports (8237A-5)

| Port | Register | Access |

|---|---|---|

| 0x00 | Channel 0 Address | R/W |

| 0x01 | Channel 0 Count | R/W |

| 0x02 | Channel 1 Address | R/W |

| 0x03 | Channel 1 Count | R/W |

| 0x04 | Channel 2 Address | R/W |

| 0x05 | Channel 2 Count | R/W |

| 0x06 | Channel 3 Address | R/W |

| 0x07 | Channel 3 Count | R/W |

| 0x08 | Status Register | R |

| 0x08 | Command Register | W |

| 0x09 | Request Register | W |

| 0x0A | Mask Register | W |

| 0x0B | Mode Register | W |

| 0x0C | Clear Flip-Flop | W |

| 0x0D | Master Clear | W |

| 0x0E | Clear Mask Register | W |

| 0x0F | Write All Mask Bits | W |

Page Registers

The DMA page registers are not part of the 8237 itself, but are implemented on the motherboard. They are provided here for convenience.

Note: The page register addresses are mapped out of order from their respective channels. Take note of the assignments.

- 0x81: Channel 2 Page Register (Address bits 16-19)

- 0x82: Channel 3 Page Register (Address bits 16-19)

- 0x83: Channel 1 Page Register (Address bits 16-19)

The IBM AT added a page register for Channel 0, but this is not implemented on the PC/XT:

- 0x87: Channel 0 Page (bits 16-19)

8288 Bus Controller

8284 Clock/Ready Generator

DIP switches

The Keyboard Interface

The DMA Page Registers

DRAM Refresh

DMA and Ready Generation

Floppy Drive Controller

IBM PC/XT systems outfitted with a floppy drive had an “IBM 5.25” Diskette Drive Adapter“ card installed in one of the available expansion slots.

For a good look at the Diskette Drive Adapter, see minuszerodegrees.net.

The IBM floppy drive controller, as we’ll refer to it here, was a collection of 74-series logic chips and a 16.0Mhz clock crystal supporting the “brain” of the card, a NEC µPD765A (NEC 765) floppy drive controller chip. It could support up to four floppy disk drives, although configurations of more than two were uncommon. Drives 0-3 would be assigned the drive letters A-D. It would feel a bit wrong to have a floppy disk as drive C, but if you did indeed have three drives connected, that’s what you’d end up with.

The NEC 765 takes an 8MHz clock, divided once from the card’s 16Mhz crystal.

The IBM controller card adds a main control register external to the 765, called the Digital Output Register or DOR. The DOR has several functions - it selects a specific drive as the target of operations, it can reset the 765, it can enable or disable interrupts and DMA, and it can turn on and off the attached floppy drive motors.

Figure 1: The Digital Output Register (DOR)

Drive Selection Bits

The two least significant bits (Bits 0-1) of the DOR control which floppy drive is selected:

| Bit 1 | Bit 0 | Selected Drive |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | Drive A |

| 0 | 1 | Drive B |

| 1 | 0 | Drive C |

| 1 | 1 | Drive D |

If a drive’s motor is not on, selecting it in the DOR will do nothing until the motor is turned on.

The DOR is implemented with an 74LS273 8-bit register chip. The DOR is write-only.

The FDC RESET bit 2 directly toggles the 765’s RST pin, resetting the controller chip.

Note: To avoid confusion, be aware that the DOR is the only drive selection method used by the IBM floppy drive controller. The NEC 765 command set includes fields that would, in theory, select which drive the operation is intended to target. Under IBM’s controller design, these bits do nothing - the 765 is not in control of which drive is selected. You can verify this yourself by noting the 765’s “unit select” pins, 28 and 29, are not connected.

On the IBM PC/XT, the floppy drive controller is operated by the BIOS in DMA mode exclusively. It is possible to operate the controller in polled-io mode in a manual fashion, but there are severe disadvantages to doing so - as was seen on the IBM PCjr which lacked a DMA controller. The lack of DMA prevented such operations as transferring data via the serial ports and floppy disk drive at the same time.

I/O Ports

The IBM Diskette Drive Adapter decodes the following IO port addresses:

| PC Port | 765 Port | RW | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0x3F2 | n/a | W | Digital Output Register |

| 0x3F4 | 0 | R | µPD765A Status Register |

| 0x3F5 | 1 | RW | µPD765A Data Register |

DMA Channel

The IBM Diskette Drive Adapter uses DMA Channel 2.

IRQs

The IBM Diskette Drive Adapter uses IRQ 6.

Technical References

References

-

(minuszerodegrees.net) IBM 5-1/4“ Diskette Drive Adapter. IBM Corporation. Document Number: 6361505. ↩

Hard Disk Controllers

IBM/Xebec Hard Disk Controler

XTIDE

The Motorola 6845 CRTC

Monochrome Display Adapter (MDA)

The IBM Color Graphics Adapter (CGA)

The IBM CGA card was one of the first video adapters available for the IBM PC/XT, along with the IBM Monochrome Display Adapter and the Hercules video adapter.

The CGA could be connected to a regular North American television set via its composite output connector. A digital DE-9 connection eventually allowed it to be connected to the IBM 5153 Color Display, once that was finally released. IBM left owners of the CGA waiting a bit for a proper monitor - it was only released in 1983, two years after the CGA’s debut.

The CGA has 16KB of DRAM dedicated to video memory, and a 4KB font ROM that holds bit patterns for drawing text glyphs.

In text mode, the CGA card was capable of outputting 16 colors. In graphics mode, it was limited to 3 palettes of 3 fixed colors each, with a selectable background color. The CGA also had a high-resolution mode, with a single, selectable foreground color on black.

Like the MDA, the CGA is built around the Motorola MC6845 CRTC. See that section first for a basic understanding of how that chip is used to define display geometry.

Display Timings

Unlike the MDA, the CGA does not have its own crystal. IBM designed the main system crystal of the PC itself around the NTSC display standard with the apparent intent of simplifying the production of the CGA and other television-compatible peripherals.

The 5150 has a single main system crystal with a frequency of 14.31818MHz. This frequency is exactly four times the NTSC color subcarrier frequency.

The crystal frequency can be expressed as a fraction:

$$f_{crystal} = \frac{315}{22} \text{ MHz} = 14.318181\overline{81} \text{ MHz}$$

The CGA’s output is almost but not quite entirely NTSC-conforming. A real NTSC signal provides two interlaced fields of 262.5 scanlines, whereas the CGA outputs 262 progressive scanlines at approximately 60fps. This 565 vs 564 scanline difference is minor enough for television sets to ignore.

The CGA produces a display field of \(912 \times 262\) or \(238,944\) hdots.

The true refresh rate of the CGA can be calculated as:

$$f_{refresh} = \frac{14{,}318{,}181}{238{,}944} = 59.92 \text{ Hz}$$

This is 99.87% of 60Hz, meaning that if you sync your emulator to 60Hz you will run about 0.1% too fast.

Video Memory

The 16KB of DRAM the CGA card has is not expandable. It also single-ported, meaning that only either the CPU or the CGA can access the video memory at any given time. This is a bit of a problem, as the CGA needs to be reading video memory constantly as it rasterizes the screen.

The CGA has some circuitry for attempting to marshall the CPU’s access to video memory, but perhaps due to limitations in board space, this circuitry was only implemented for the card’s slower low-resolution modes. In high-resolution text mode, attempts to access video memory by the CPU while the CGA is rasterizing the active display area will result in what is called “snow” - random glitches where the CGA reads the wrong data while attempting to read character glyphs or attribute bytes. IBM worked around this in BIOS routines that scrolled the screen - such as when you execute the DIR command in DOS by rapidly disabling and re-enabling the display, causing noticable flicker.

Video Memory and Timing

Keyboard

The IBM 5150 and 5160 originally used an 83-key IBM “Model F” keyboard1, IBM Part #1501100 (Part #1501105 in the UK2).

Later revisions of the BIOS ROM for the IBM 5160 contained support for the 101-key Enhanced Keyboard3. This keyboard introduced multi-byte scancodes, which required large changes in the keyboard handling code of the BIOS to accommodate.

IBM changed the keyboard protocol with the IBM 5170 AT, making everyone buy new keyboards. Therefore, keyboards of this era are often described as speaking either the “XT” or “AT” protocol. Some keyboards were made that could switch between both, and adapters were (and are) available.

The 83-key keyboard layout is missing many of the keys that we take for granted on modern keyboard layouts. Unlike modern keyboards, the function keys are arranged in a block on the left side.

Figure 1.1: IBM PC 83-key Model F Keyboard Layout with scancodes (Click to zoom)

Keyboard Operation

The keyboard communicates with the PC by sending scancodes when a key is pressed or released. On the original 83-key keyboard, each key produces a pair of single-byte scancodes, one when pressed, called the make scancode, and one when released called the break scancode. The make scancodes are typically the values provided in scancode tables, and can be seen in the figure above. Break scancodes are calculated by taking the make scancode and setting the MSB to 1.

Since keyboard operation is event-driven, if the host computer were ever to miss processing a ‘key-up’ scancode, this would cause the phenomenon of a “stuck key,” something most PC users have experienced at one point.

Inside the Model F keyboard is an Intel 8048 microcontroller that is responsible for scanning the internal key matrix and converting keypresses (and releases) into scancodes to send to the host PC. On early versions of the Model F, the 8048 could be reset directly through the RESET pin on the keyboard DIN connector. Later versions of the Model F disconnected this RESET line and the 8048 is no longer externally resettable, except perhaps by unplugging the keyboard.

The 8048 has burned-in program ROM and a small amount of onboard RAM, in which it keeps a 16-byte scancode FIFO buffer. Scancodes are placed into this buffer as they are detected from the keyboard matrix, and read out as they are sent to the host.

Note: It is important that you buffer scancodes in your emulator - a fast typist can generate scancodes very rapidly - consider how quickly scancodes may be produced in the event that multiple keys are pressed and released at once. It is generally insufficient to deliver one scancode per frame.

The keyboard is a serial device, and the keyboard port is a specialized serial port. The exact electrical details of the keyboard port are not crucially important to emulating the keyboard, except for the operation of the clock pin.

Bit 6 of the 8255 PPI’s Port B register, when set to 0, will pull the keyboard clock line low. When held in this state for approximately 20ms, the 8048 will perform a keyboard self-test. When the clock line is released by writing 1 to PPI Port B bit 6, the keyboard will send the special scancode 0xAA. If the keyboard internally detects a physically stuck key, it will send the scancode of that key 10ms after sending 0xAA.4.

If you fail to emulate sending the reset scancode 0xAA at the appropriate time, the BIOS will emit a POST error code 301.

Note that the ‘clock’ line does not actually clock the 8048. The keyboard data and clock lines are simply connected to specialized I/O pins on the 8048 that it can monitor. The 8048 is clocked via an internal oscillator configured for approximately 5MHz.

Typematic Repeat

Most computer users are familiar with what happens when a key on the keyboard is held down - typically after a short delay, the keyboard will begin repeating the keypress automatically.

IBM called this feature “typematic” on the Model F. When a key is held down, it will start to repeat after approximately 500ms at a rate of approximately 11 characters per second. Both the make and break scancodes are sent for each repeat.

It is possible to simply pass through the host’s typematic repeat to your emulator, but I recommend handling it yourself, as it gives you better control over the rate (which might otherwise be too fast).

There are some subtleties to typematic repeat operation:

- If more than one key is held down, only the last key will repeat.

- Repeat will stop when a key is released, even if other keys remain held down.

The IBM BIOS keyboard routines will filter typematic events for Ctrl, Shift, Alt, Num Lock, Scroll Lock, Caps Lock, and Insert. If the default BIOS keyboard routines are used by an application that does not process keyboard events fast enough, it is likely that holding down a key will fill the BIOS keyboard buffer and result in several angry beeps from the PC speaker.

The Keyboard Interface

Serial data from the keyboard is first read into a shift register on the motherboard, then ultimately read out in a parallel fashion via the 8255 PPI’s Port A. See the chapter on the IBM PC’s Keyboard Interface for more details.

SDL Scancode Table

If you happen to be using SDL for your emulator, here’s a table of SDL keycode definitions to IBM scancodes:

| SDL Key | Scancode (hex) |

|---|---|

| SDLK_A | 1E |

| SDLK_B | 30 |

| SDLK_C | 2E |

| SDLK_D | 20 |

| SDLK_E | 12 |

| SDLK_F | 21 |

| SDLK_G | 22 |

| SDLK_H | 23 |

| SDLK_I | 17 |

| SDLK_J | 24 |

| SDLK_K | 25 |

| SDLK_L | 26 |

| SDLK_M | 32 |

| SDLK_N | 31 |

| SDLK_O | 18 |

| SDLK_P | 19 |

| SDLK_Q | 10 |

| SDLK_R | 13 |

| SDLK_S | 1F |

| SDLK_T | 14 |

| SDLK_U | 16 |

| SDLK_V | 2F |

| SDLK_W | 11 |

| SDLK_X | 2D |

| SDLK_Y | 15 |

| SDLK_Z | 2C |

| SDLK_1 | 02 |

| SDLK_2 | 03 |

| SDLK_3 | 04 |

| SDLK_4 | 05 |

| SDLK_5 | 06 |

| SDLK_6 | 07 |

| SDLK_7 | 08 |

| SDLK_8 | 09 |

| SDLK_9 | 0A |

| SDLK_0 | 0B |

| SDLK_RETURN | 1C |

| SDLK_ESCAPE | 01 |

| SDLK_BACKSPACE | 0E |

| SDLK_TAB | 0F |

| SDLK_SPACE | 39 |

| SDLK_MINUS | 0C |

| SDLK_EQUALS | 0D |

| SDLK_LEFTBRACKET | 1A |

| SDLK_RIGHTBRACKET | 1B |

| SDLK_BACKSLASH | 2B |

| SDLK_SEMICOLON | 27 |

| SDLK_APOSTROPHE | 28 |

| SDLK_COMMA | 33 |

| SDLK_PERIOD | 34 |

| SDLK_SLASH | 35 |

| SDLK_GRAVE | 29 |

| SDLK_LSHIFT | 2A |

| SDLK_RSHIFT | 36 |

| SDLK_LCTRL | 1D |

| SDLK_RCTRL | 1D |

| SDLK_LALT | 38 |

| SDLK_RALT | 38 |

| SDLK_CAPSLOCK | 3A |

| SDLK_F1 | 3B |

| SDLK_F2 | 3C |

| SDLK_F3 | 3D |

| SDLK_F4 | 3E |

| SDLK_F5 | 3F |

| SDLK_F6 | 40 |

| SDLK_F7 | 41 |

| SDLK_F8 | 42 |

| SDLK_F9 | 43 |

| SDLK_F10 | 44 |

| SDLK_F11 | 57 |

| SDLK_F12 | 58 |

| SDLK_UP | 48 |

| SDLK_DOWN | 50 |

| SDLK_LEFT | 4B |

| SDLK_RIGHT | 4D |

| SDLK_INSERT | 52 |

| SDLK_DELETE | 53 |

| SDLK_HOME | 47 |

| SDLK_END | 4F |

| SDLK_PAGEUP | 49 |

| SDLK_PAGEDOWN | 51 |

| SDLK_KP_1 | 4F |

| SDLK_KP_2 | 50 |

| SDLK_KP_3 | 51 |

| SDLK_KP_4 | 4B |

| SDLK_KP_5 | 4C |

| SDLK_KP_6 | 4D |

| SDLK_KP_7 | 47 |

| SDLK_KP_8 | 48 |

| SDLK_KP_9 | 49 |

| SDLK_KP_0 | 52 |

| SDLK_KP_PLUS | 4E |

| SDLK_KP_MINUS | 4A |

| SDLK_KP_PERIOD | 53 |

| SDLK_KP_ENTER | 1C |

| SDLK_KP_DIVIDE | 35 |

| SDLK_KP_MULTIPLY | 37 |

| SDLK_KP_EQUALS | 0D |

References

-

wikipedia.org Model F keyboard. ↩

-

seasip.info The IBM 1501105 Keyboard ↩

-

minuszerodegrees.net IBM 5160 - Keyboards ↩

-

minuszerodegrees.net 5160 Keyboard Startup ↩

Speaker and Sound

The Cassette Interface

Serial Ports

Parallel Ports

The Game Port

Joystikcs

Mice

Microsoft Serial Mouse

Mouse Systems Serial Mouse

Light Pen

The IBM 5150 BIOS

The IBM 5160 BIOS

GLaBIOS

Emulation Architecture

CPU Emulation Techniques

Device Synchronization

Performance Optimization

Testing Strategies

Debugging Tools

Compatibility Issues

Extended ASCII Table

This table shows all 256 characters of the IBM PC’s Code Page 437 character set as rendered by the CGA’s 8x8 font.

| Dec | Hex | Oct | Char | Glyph | Dec | Hex | Oct | Char | Glyph | Dec | Hex | Oct | Char | Glyph | Dec | Hex | Oct | Char | Glyph |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 00 | 000 | NUL | 64 | 40 | 100 | @ | 128 | 80 | 200 | Ç | 192 | C0 | 300 | |||||

| 1 | 01 | 001 | SOH | 65 | 41 | 101 | A | 129 | 81 | 201 | ü | 193 | C1 | 301 | |||||

| 2 | 02 | 002 | STX | 66 | 42 | 102 | B | 130 | 82 | 202 | é | 194 | C2 | 302 | |||||

| 3 | 03 | 003 | ETX | 67 | 43 | 103 | C | 131 | 83 | 203 | â | 195 | C3 | 303 | |||||

| 4 | 04 | 004 | EOT | 68 | 44 | 104 | D | 132 | 84 | 204 | ä | 196 | C4 | 304 | |||||

| 5 | 05 | 005 | ENQ | 69 | 45 | 105 | E | 133 | 85 | 205 | à | 197 | C5 | 305 | |||||

| 6 | 06 | 006 | ACK | 70 | 46 | 106 | F | 134 | 86 | 206 | å | 198 | C6 | 306 | |||||

| 7 | 07 | 007 | BEL | 71 | 47 | 107 | G | 135 | 87 | 207 | ç | 199 | C7 | 307 | |||||

| 8 | 08 | 010 | BS | 72 | 48 | 110 | H | 136 | 88 | 210 | ê | 200 | C8 | 310 | |||||

| 9 | 09 | 011 | TAB | 73 | 49 | 111 | I | 137 | 89 | 211 | ë | 201 | C9 | 311 | |||||

| 10 | 0A | 012 | LF | 74 | 4A | 112 | J | 138 | 8A | 212 | è | 202 | CA | 312 | |||||

| 11 | 0B | 013 | VT | 75 | 4B | 113 | K | 139 | 8B | 213 | ï | 203 | CB | 313 | |||||

| 12 | 0C | 014 | FF | 76 | 4C | 114 | L | 140 | 8C | 214 | î | 204 | CC | 314 | |||||

| 13 | 0D | 015 | CR | 77 | 4D | 115 | M | 141 | 8D | 215 | ì | 205 | CD | 315 | |||||

| 14 | 0E | 016 | SO | 78 | 4E | 116 | N | 142 | 8E | 216 | Ä | 206 | CE | 316 | |||||

| 15 | 0F | 017 | SI | 79 | 4F | 117 | O | 143 | 8F | 217 | Å | 207 | CF | 317 | |||||

| 16 | 10 | 020 | DLE | 80 | 50 | 120 | P | 144 | 90 | 220 | É | 208 | D0 | 320 | |||||

| 17 | 11 | 021 | DC1 | 81 | 51 | 121 | Q | 145 | 91 | 221 | æ | 209 | D1 | 321 | |||||

| 18 | 12 | 022 | DC2 | 82 | 52 | 122 | R | 146 | 92 | 222 | Æ | 210 | D2 | 322 | |||||

| 19 | 13 | 023 | DC3 | 83 | 53 | 123 | S | 147 | 93 | 223 | ô | 211 | D3 | 323 | |||||

| 20 | 14 | 024 | DC4 | 84 | 54 | 124 | T | 148 | 94 | 224 | ö | 212 | D4 | 324 | |||||

| 21 | 15 | 025 | NAK | 85 | 55 | 125 | U | 149 | 95 | 225 | ò | 213 | D5 | 325 | |||||

| 22 | 16 | 026 | SYN | 86 | 56 | 126 | V | 150 | 96 | 226 | û | 214 | D6 | 326 | |||||

| 23 | 17 | 027 | ETB | 87 | 57 | 127 | W | 151 | 97 | 227 | ù | 215 | D7 | 327 | |||||

| 24 | 18 | 030 | CAN | 88 | 58 | 130 | X | 152 | 98 | 230 | ÿ | 216 | D8 | 330 | |||||

| 25 | 19 | 031 | EM | 89 | 59 | 131 | Y | 153 | 99 | 231 | Ö | 217 | D9 | 331 | |||||

| 26 | 1A | 032 | SUB | 90 | 5A | 132 | Z | 154 | 9A | 232 | Ü | 218 | DA | 332 | |||||

| 27 | 1B | 033 | ESC | 91 | 5B | 133 | [ | 155 | 9B | 233 | ¢ | 219 | DB | 333 | |||||

| 28 | 1C | 034 | FS | 92 | 5C | 134 | \ | 156 | 9C | 234 | £ | 220 | DC | 334 | |||||

| 29 | 1D | 035 | GS | 93 | 5D | 135 | ] | 157 | 9D | 235 | ¥ | 221 | DD | 335 | |||||

| 30 | 1E | 036 | RS | 94 | 5E | 136 | ^ | 158 | 9E | 236 | ₧ | 222 | DE | 336 | |||||

| 31 | 1F | 037 | US | 95 | 5F | 137 | _ | 159 | 9F | 237 | ƒ | 223 | DF | 337 | |||||

| 32 | 20 | 040 | Space | 96 | 60 | 140 | ` | 160 | A0 | 240 | á | 224 | E0 | 340 | α | ||||

| 33 | 21 | 041 | ! | 97 | 61 | 141 | a | 161 | A1 | 241 | í | 225 | E1 | 341 | ß | ||||

| 34 | 22 | 042 | " | 98 | 62 | 142 | b | 162 | A2 | 242 | ó | 226 | E2 | 342 | Γ | ||||

| 35 | 23 | 043 | # | 99 | 63 | 143 | c | 163 | A3 | 243 | ú | 227 | E3 | 343 | π | ||||

| 36 | 24 | 044 | $ | 100 | 64 | 144 | d | 164 | A4 | 244 | ñ | 228 | E4 | 344 | Σ | ||||

| 37 | 25 | 045 | % | 101 | 65 | 145 | e | 165 | A5 | 245 | Ñ | 229 | E5 | 345 | σ | ||||

| 38 | 26 | 046 | & | 102 | 66 | 146 | f | 166 | A6 | 246 | ª | 230 | E6 | 346 | µ | ||||

| 39 | 27 | 047 | ' | 103 | 67 | 147 | g | 167 | A7 | 247 | º | 231 | E7 | 347 | τ | ||||

| 40 | 28 | 050 | ( | 104 | 68 | 150 | h | 168 | A8 | 250 | ¿ | 232 | E8 | 350 | Φ | ||||

| 41 | 29 | 051 | ) | 105 | 69 | 151 | i | 169 | A9 | 251 | 233 | E9 | 351 | Θ | |||||

| 42 | 2A | 052 | * | 106 | 6A | 152 | j | 170 | AA | 252 | ¬ | 234 | EA | 352 | Ω | ||||

| 43 | 2B | 053 | + | 107 | 6B | 153 | k | 171 | AB | 253 | ½ | 235 | EB | 353 | δ | ||||

| 44 | 2C | 054 | , | 108 | 6C | 154 | l | 172 | AC | 254 | ¼ | 236 | EC | 354 | ∞ | ||||

| 45 | 2D | 055 | - | 109 | 6D | 155 | m | 173 | AD | 255 | ¡ | 237 | ED | 355 | φ | ||||

| 46 | 2E | 056 | . | 110 | 6E | 156 | n | 174 | AE | 256 | « | 238 | EE | 356 | ε | ||||

| 47 | 2F | 057 | / | 111 | 6F | 157 | o | 175 | AF | 257 | » | 239 | EF | 357 | ∩ | ||||

| 48 | 30 | 060 | 0 | 112 | 70 | 160 | p | 176 | B0 | 260 | 240 | F0 | 360 | ≡ | |||||

| 49 | 31 | 061 | 1 | 113 | 71 | 161 | q | 177 | B1 | 261 | 241 | F1 | 361 | ± | |||||

| 50 | 32 | 062 | 2 | 114 | 72 | 162 | r | 178 | B2 | 262 | 242 | F2 | 362 | ≥ | |||||

| 51 | 33 | 063 | 3 | 115 | 73 | 163 | s | 179 | B3 | 263 | 243 | F3 | 363 | ≤ | |||||

| 52 | 34 | 064 | 4 | 116 | 74 | 164 | t | 180 | B4 | 264 | 244 | F4 | 364 | ||||||

| 53 | 35 | 065 | 5 | 117 | 75 | 165 | u | 181 | B5 | 265 | 245 | F5 | 365 | ||||||

| 54 | 36 | 066 | 6 | 118 | 76 | 166 | v | 182 | B6 | 266 | 246 | F6 | 366 | ÷ | |||||

| 55 | 37 | 067 | 7 | 119 | 77 | 167 | w | 183 | B7 | 267 | 247 | F7 | 367 | ≈ | |||||

| 56 | 38 | 070 | 8 | 120 | 78 | 170 | x | 184 | B8 | 270 | 248 | F8 | 370 | ° | |||||

| 57 | 39 | 071 | 9 | 121 | 79 | 171 | y | 185 | B9 | 271 | 249 | F9 | 371 | ∙ | |||||

| 58 | 3A | 072 | : | 122 | 7A | 172 | z | 186 | BA | 272 | 250 | FA | 372 | · | |||||

| 59 | 3B | 073 | ; | 123 | 7B | 173 | { | 187 | BB | 273 | 251 | FB | 373 | √ | |||||

| 60 | 3C | 074 | < | 124 | 7C | 174 | | | 188 | BC | 274 | 252 | FC | 374 | ⁿ | |||||

| 61 | 3D | 075 | = | 125 | 7D | 175 | } | 189 | BD | 275 | 253 | FD | 375 | ² | |||||

| 62 | 3E | 076 | > | 126 | 7E | 176 | ~ | 190 | BE | 276 | 254 | FE | 376 | ■ | |||||

| 63 | 3F | 077 | ? | 127 | 7F | 177 | 191 | BF | 277 | 255 | FF | 377 |

Notable Characters

Control Characters (0x00-0x1F)

In the IBM PC character set, the control characters have glyphs mapped to them. These characters were often used in games. The two smiley faces are perhaps the most famous - they played the role of the player character in innumerable video games, such as Rogue.

| Dec | Hex | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 00 | Null (displays as blank) |

| 1 | 01 | Smiley face |

| 2 | 02 | Inverse smiley face |

| 3 | 03 | Heart |

| 4 | 04 | Diamond |

| 5 | 05 | Club |

| 6 | 06 | Spade |

| 7 | 07 | Bullet (BEL character) |

| 13 | 0D | Musical note (CR character) |

Box Drawing Characters (0xB0-0xDF)

The IBM PC character set includes an extensive set of box-drawing characters used for creating text-mode user interfaces. These include single-line, double-line, and mixed box corners and intersections.

Mathematical and Greek Symbols (0xE0-0xFF)

The upper range includes mathematical symbols and Greek letters commonly used in technical documentation:

| Dec | Hex | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 224 | E0 | Alpha |

| 225 | E1 | Beta |

| 227 | E3 | Pi |

| 228 | E4 | Sigma (uppercase) |

| 229 | E5 | Sigma (lowercase) |

| 230 | E6 | Mu |

| 241 | F1 | Plus-minus |

| 246 | F6 | Division |

| 248 | F8 | Degree |

| 253 | FD | Superscript 2 |